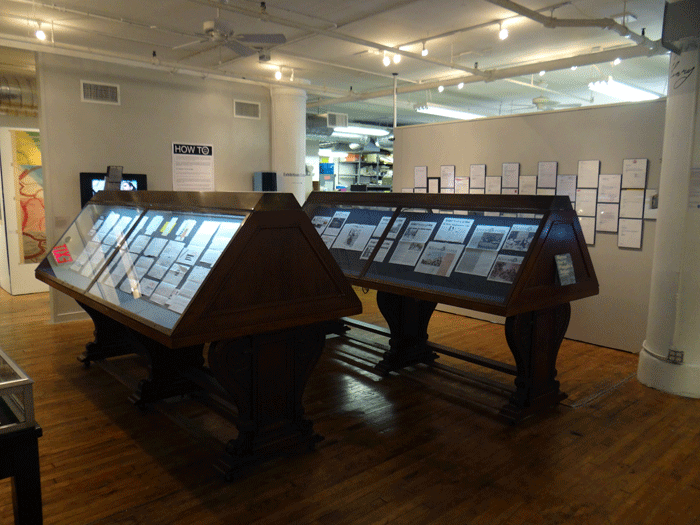

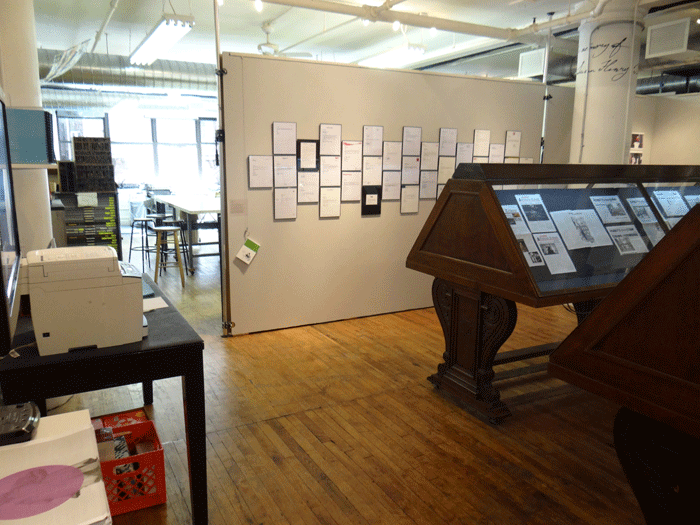

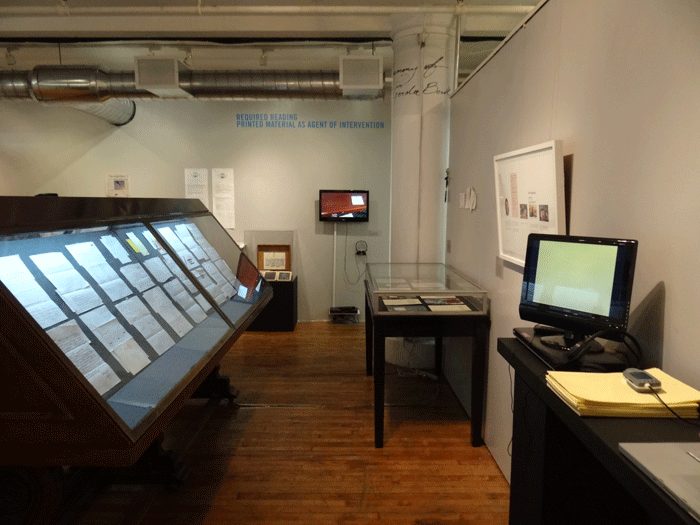

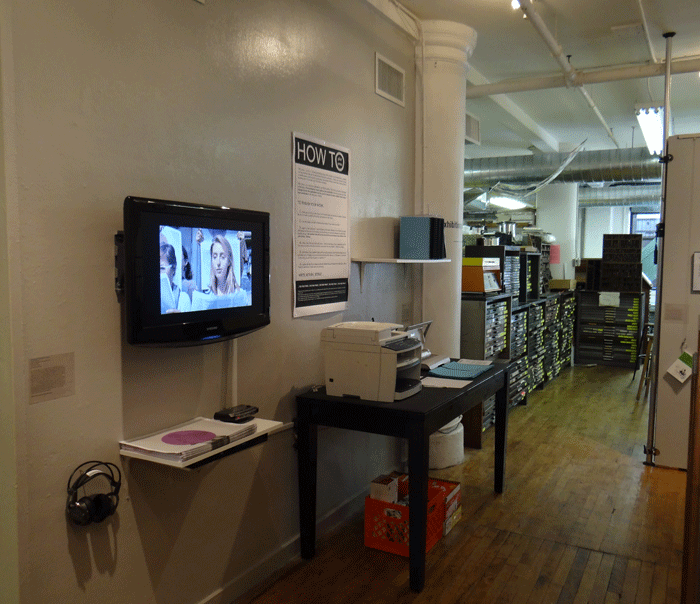

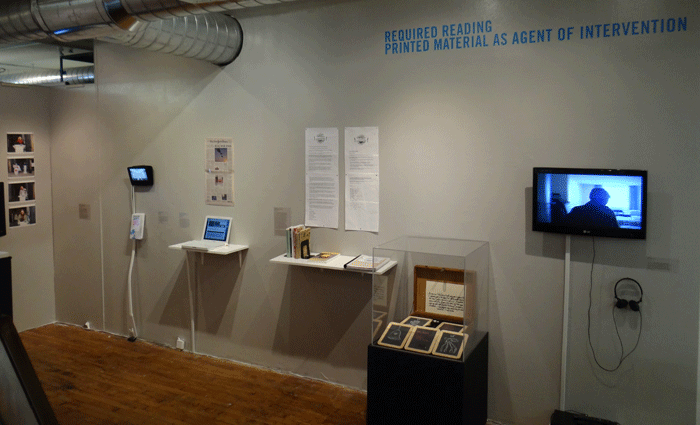

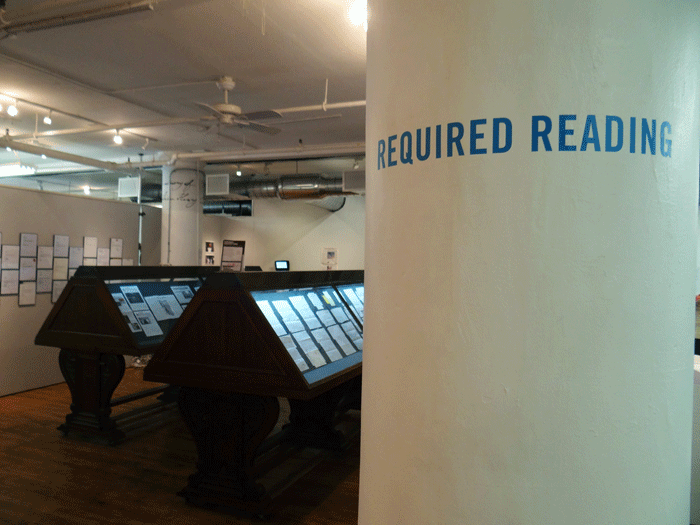

REQUIRED READING: Printed Material as Agent of Intervention

October 3 - December 15, 2012 | Center for Book Arts, New York

Artists & Projects:

Amy Balkin; AREA Chicago (Samuel Barnett, Euan Hague, Jayne Hileman, Dave Pabelllon, Daniel Tucker, and Rebecca Zorach); Yevgeniy Fiks; Pablo Helguera; Marisa Jahn (REV-) with Street Vendor Project of the Urban Justice Center; Packard Jennings; Jen Kennedy and Liz Linden; Steve Lambert and Andy Bichlbaum of The Yes Men (with 30 writers, 50 advisors, 1,000 volunteer distributors, CODEPINK, May First/People Link, Evil Twin, Improv Everywhere, and Not An Alternative); Lize Mogel with Mara Cherkasky, John Cloud, and Ryan Shepard; Queerocracy and Carlos Motta; Occupied Newspapers (The Boston Occupier, The Occupied Times of London, The Occupied Oakland Tribune, Occupy Pittsburgh Now, and The Occupied Wall Street Journal); Sheryl Oring; Dread Scott; S.W.A.M.P. (Matt Kenyon with Doug Easterly); and Temporary Services, Tamms Year Ten and Sarah Ross

Overview:

Required Reading: Printed Material as Agent of Intervention presents fifteen projects that range from published books and correspondence to performance and video documentation, and are meant to challenge a political or social issue. The works in this exhibition demonstrate the ability of printed materials to act as symbols of ideologies and beliefs. They are used by the participating artists as social agents—intervening in public space to expose an audience to new opportunities and alternative concepts. In a culture where visual noise is inescapable, printed matter provides an opportunity to pause, grasp, ruminate, and pass along. We use it to educate ourselves and others, to create a gash in a stagnant situation, articulate a new context, and imagine our society as it can and should be.

*This exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue (designed by Andre Bassuet) with essays by yours truly and Howard Zinn. It is available for purchase via CBA and here.

Curatorial Statement:

So long as war and injustice remain, artists will find ways to make their art follow Shakespeare's plea in King John: "O that my tongue were in the thunder's mouth! Then with a passion would I shake the world."

Howard Zinn, Artists in Times of War, 2003

[N]ever has experience been contradicted more thoroughly than strategic experience by tactical warfare, economic experience by inflation, bodily experience by mechanical warfare, moral experience by those in power. A generation that had gone to school on a horse-drawn streetcar now stood under the open sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath these clouds, in a field of force of destructive torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body.

Walter Benjamin, The Storyteller, 1936

Walter Benjamin's 1936 essay The Storyteller describes a post-World War I society that is incapable of communicating its experiences due to a rapid stream of information, which resulted from the trauma of war and technological advancement. Almost 80 years later, the above quote eerily encapsulates our current era of remote-controlled warfare, greedy economy and corporate-bought politics. Furthermore, we have now gone above and beyond Benjamin's observations, as the bulk of our communications have moved to the virtual sphere where one-line status updates are used to capture the essence of our personal and social experiences. It is becoming increasingly hard to access our distracted minds—our heads buried in smartphones, windows piled up on our computer screens, and books competing with interactive applications.

Of course, social networking is not all negative. It has broadened our reach, connected us with individuals we would otherwise not have known and, most significantly, sparked revolutions across the globe. Yet we sign online petitions to appease our conscious and rarely engage with their cause again, and we "Like" and Tweet matters that display our political inclinations publicly but seldom discuss them in the physical world. This is the embodiment of what Benjamin referred to as the replacement of "storytelling" with "information:" "The value of information does not survive the moment in which it was new", while storytelling "preserves and concentrates its strength and is capable of releasing it even after a long time." What is lost today, therefore, is the lasting affect of the knowledge we impart about the world and ourselves.

Recent social movements have brought us back into dialogue with each other on the streets and squares of our cities, but the question remains – how do we reach those who do not come willingly? One answer put forth by the creative community has been the practice of interventions. Terms like "relational art" and "social practice" have been established in the past decade or so to describe a process in which artists directly engage with the public to raise social concerns and catalyze change. They do this through a multitude of methods, including collaboration with communities, pedagogy, performance, and disruption of cultural networks and spaces.

This brings us to Required Reading. The projects included in this exhibition use printed material to intervene in public space in order to expose an audience to new and alternative concepts. The artists use books, letters, magazines, and newspapers as learning devices and a starting point for interaction. These objects inherently require commitment, patience, time and will. They are intimate and tangible, and thus less likely to be ignored. These attributes embody the tools of Benjamin's "storyteller," as they possess the ability to go against the stream of information bombarding us on a daily basis. They cut through them, forcing us to slow down and engage – first with the material in front of us, and then with the ideology it represents.

We recognize a clear precedent to these artists' practice in what can be regarded as an early form of intervention – pamphleteering. This connection is laid out in Howard Zinn's essay "Pamphleteering in America:"

The pamphlets of history are a perfect expression of the marriage of art and politics—their language is the language of the people, their cheapness makes them accessible to all, their content is revolutionary, demanding fundamental changes in society. Like all socially conscious art, they transcend the world of commerce, they transcend the orthodox, and so they are profoundly democratic.

In his short survey of the history of pamphlet distribution in America, Zinn stresses the importance and effect of this custom. He establishes this through Thomas Paine's wide-reaching 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, which called for Northern America's independence from England. This publication was printed in twenty-five editions and reached hundreds of thousands of the then-population of three million Americans. Zinn finds the roots of pivotal social revolutions in the U.S. – women's rights, abolition of slavery, anti-imperialism, class struggle – in ideas initially disseminated by pamphleteers. He clearly delineates a pamphlet's advantages: quick and inexpensive to produce, written in layman language, easy to preserve, share, and conceal.

The pamphlet's main objectives were and remain to educate the public, protest the status quo, and introduce new ideas. This description can easily be applied to a host of other printed formats. Each in their own way, the artists in Required Reading have recognized the intrinsic strength and virtue of distributing such media. The exhibition casts them in the role of social agents, and the works as symbols of ideologies and beliefs.

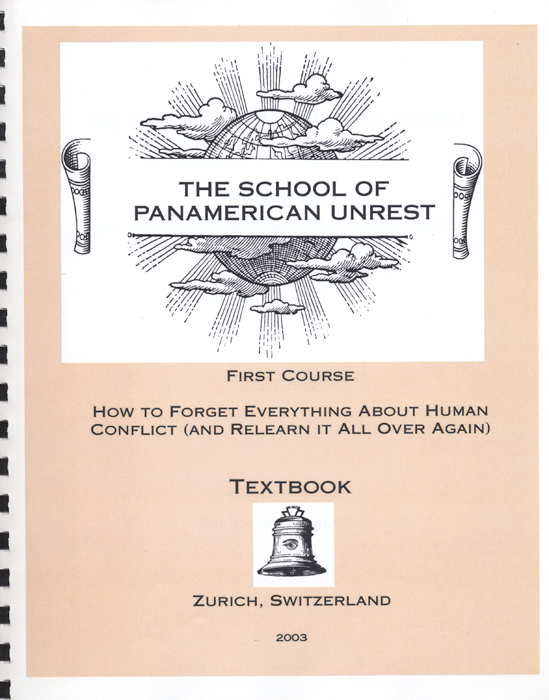

Several artists chose to utilize printed materials in order to educate a broad public on an existing issue. Amy Balkin organized a public reading of a scientific report on climate change to inform and engage a wider audience in its environmental and socio-economic ramifications. In 2003, Pablo Helguera compiled historic and current texts into a textbook that served as the pedagogical basis of his School of Panamerican Unrest, an itinerant platform dedicated to discussing the history, ideology and trends of thought that have shaped the cultural and political landscape of the Americas. Queerocracy and Carlos Motta gathered a group of individuals in Columbus Circle, New York on Columbus Day 2011 to read and distribute a timeline of significant events in the global queer and immigrant movements.

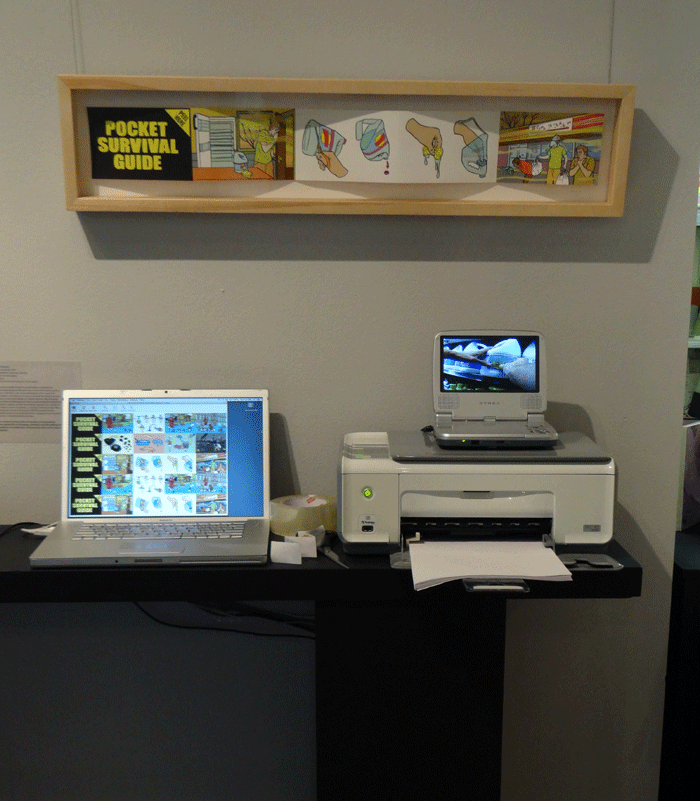

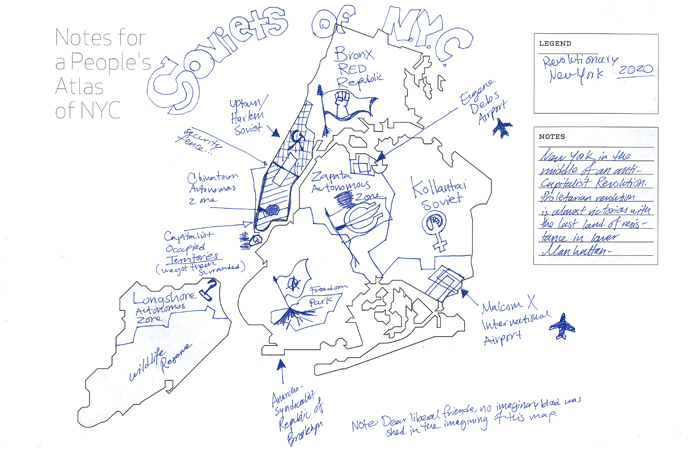

Re-envisioning the present using printed matter is a theme that also permeates through many works in the exhibition. In 2008, Steve Lambert in collaboration with Andy Bichlbaum of The Yes Men and dozens of organizations and writers produced a faux special edition of the New York Times that reimagined our future based on a positive vision of where we want our society to be on July 4, 2009. The collective AREA Chicago developed a community map-making project that calls upon residents of various cities to fill in a blank map of their town with information that is significant to them. Packard Jennings created a graphic pamphlet for individuals to covertly affix to plastic packaging in stores, offering ways that the object can be re-used in the event of an ecological disaster.

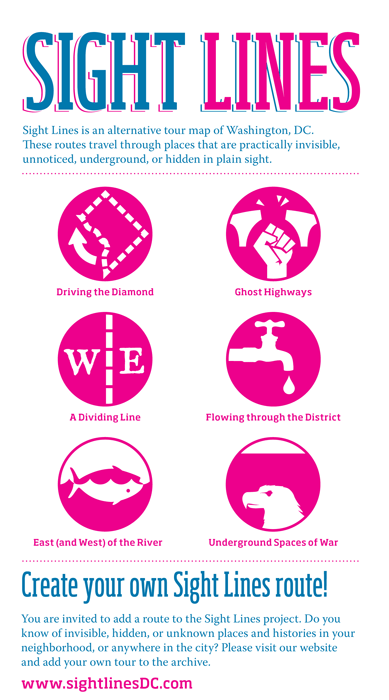

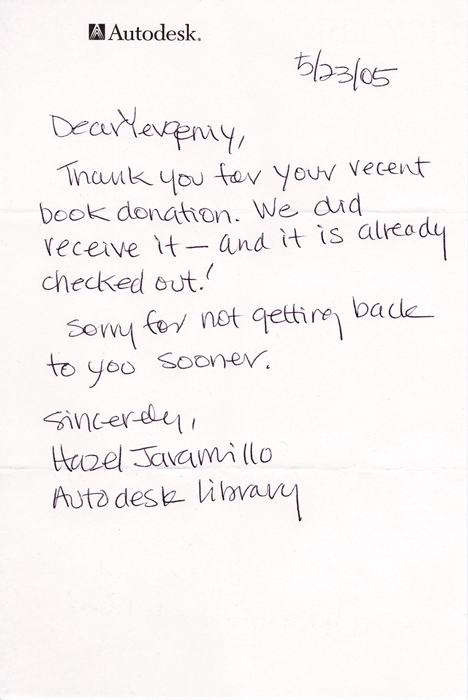

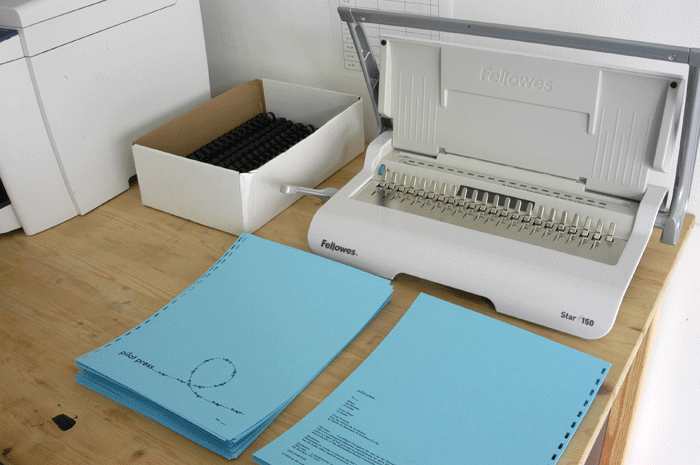

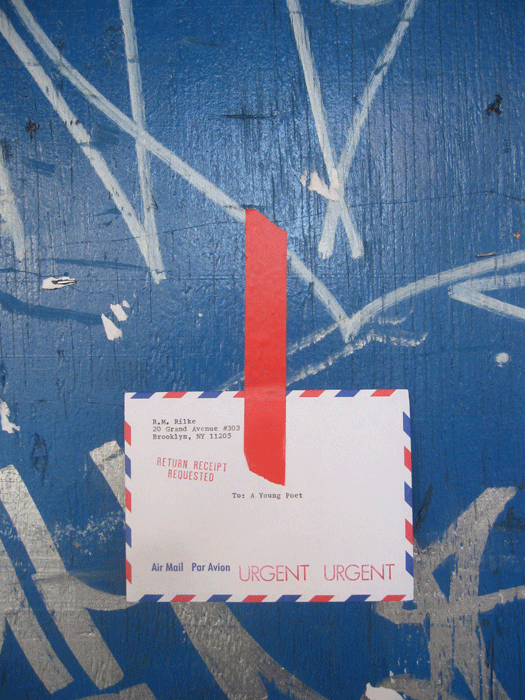

Other works re-contextualize issues via the production and dissemination of books, newspapers, maps, and letters. Sheryl Oring placed envelopes around Manhattan that contained an excerpt from Rainer Maria Rilke's Letters to a Young Poet originally written to a man trying to choose between a career as a poet or a soldier. Jen Kennedy and Liz Linden formed a D.I.Y imprint devoted to feminist works to counter the traditional view of feminism as a movement of the past that lacks contemporary resonance. Yevgeniy Fiks mailed a hundred copies of Lenin's pamphlet Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917) to some of the world's major corporations requesting to donate it to their libraries. Many of the newspapers that grew out of the Occupy Movement have outlasted the stage of spatial occupation to function as an independent journalistic source that offers an alternative to corporate-run media. Lize Mogel created a tour map of Washington, D.C. delineating an alternative view of the iconic city with six different routes that pass through predominantly mundane or unfamiliar terrain.

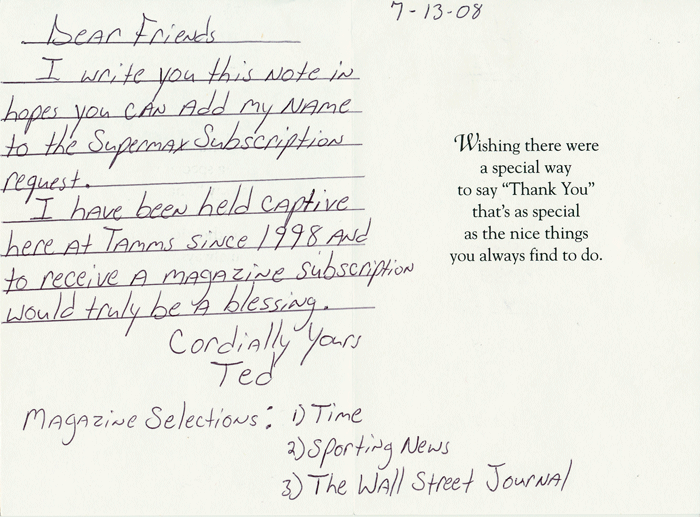

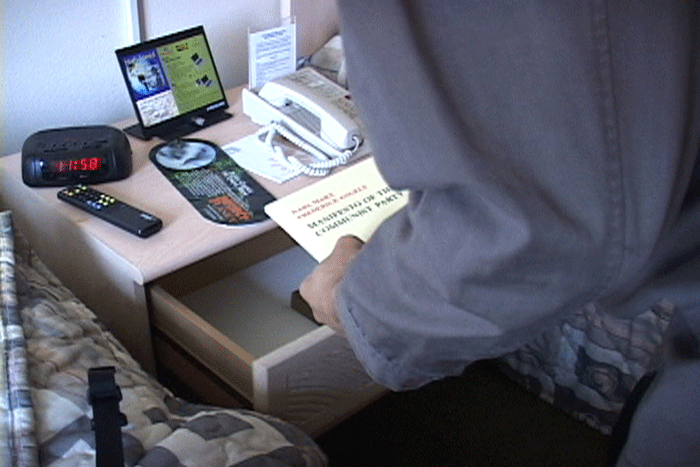

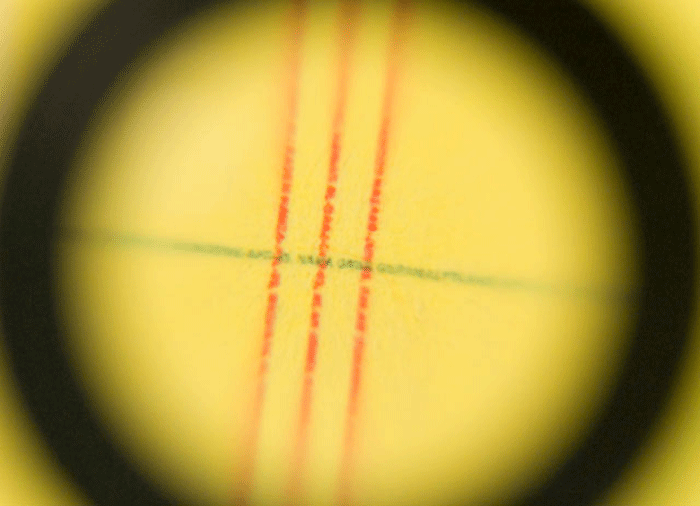

Printed matter is often used as a tool for dissent within a pertinent location or setting. Marisa Jahn with Street Vendor Project served an NYC councilwoman with 500 violation tickets to protest her 2010 proposal to revoke the vending permit of food trucks that accumulate more than three parking tickets a year. Dread Scott placed a copy of the Communist Manifesto alongside the New Testament in desk drawers of various hotel rooms across the country.. The collaborative duo S.W.A.M.P. microprinted onto yellow notepads the names and death dates of Iraqi civilian casualties since 2003, and covertly distributed them to members of the U.S. Congress and Senate. Tamms Year Ten, Temporary Services and Sarah Ross initiated Supermax Subscriptions, a program that converts donated frequent flier miles into magazine subscriptions for prisoners in solitary confinement at Illinois' Tamms CMAX Supermax Prison.

In a culture where visual noise is inescapable, printed matter provides an opportunity to pause, grasp, ruminate, and pass along. We use it to educate ourselves and others, to create a gash in a stagnant situation, articulate a new context, and envision our society as it can and should be. The thesis of this exhibition can find no better closing than a quote from a response letter written to the coordinators of Supermax Subscriptions by Jesus M., a Tamms CMAX prisoner, which encapsulates the show's spirit, and articulates what should be the ultimate objective of any artist:

Greetings My Friends,

First and foremost I would like to commend you on a Project well-put together. It is a work of Art and not only an expression of creative ingenuity but even Higher yet,

a gesture of sincere humanity.

- Yaelle Amir, August 26, 2012